In February 2021, I delivered a short lecture titled "A Black Plantswoman in the 21st Century." In that talk, I highlighted the disconnection between the portrayal of Central Park by its designer and the reality of the park's creation, spatially linked the historic racialized displacement of Seneca Village to a racially antagonistic incident on May 5, 2020 in the Ramble, and spoke about the Black women on what I call my botanical throughline. In light of the celebration of the 200th birthday of Frederick Law Olmsted this year, I thought I would issue my talk as an essay tying the dislocation of Seneca Village residents to my discovery of my botanical groove.

Frederick Law Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822. He was born in Hartford, CT, described enslavement in the U.S. South as a journalist for the Daily Times, and developed the idea of the North American urban park after a visit to Birkenhead Park in London. Olmsted and Calvert Vaux submitted the winning design for Central Park in 1858. The title of "father of landscape architecture" was applied posthumously, I think, but the opening of Central Park in 1859 and Prospect Park in 1867 established the two men as the favored park designers.

Olmsted believed parks were antidotes to city life; they would provide mental restoration from the exhausting pace and dulling nature of urban life. He envisioned Central Park as a place to foster social reform through the mingling of the classes. Despite his reporting on slavery in southern states, to my knowledge Olmsted did not reference African Americans or the role of race in his writings about urban parks. He did argue that the urban park was a space to practice and reinforce democratic ideals. By not explicitly talking about racist animosity and segregation of public space and by not denouncing the destruction of the Black community on what would become part of the park, Olmsted's rhetoric about the park as an equalizing landscape wasn't true at the founding of Central Park, and has fallen apart at various points in the park's existence.

|

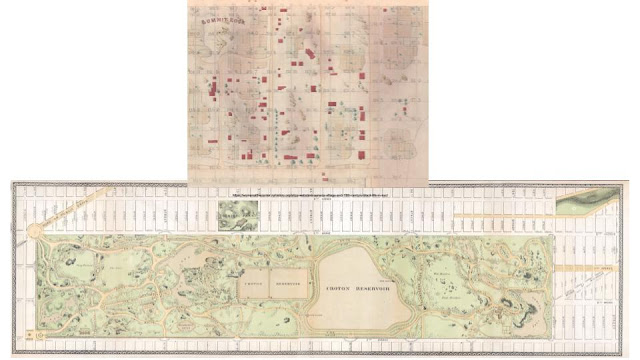

| Images of Seneca Village (top; source) and the Central Park Greensward Plan |

The Black enclave of Seneca Village was razed in 1857 to facilitate the construction of Central Park. Seneca Village was home to a majority African-descended population. The community supported schools, cemeteries, churches, and businesses. In addition, "twenty percent of the city’s 71 Black landowners and ten percent of its eligible owners” (Charlot 2014). The ownership of property valued at at least $250 was a voting requirement in New York State (Charlot 2014). Seneca Village was created by African Americans in 1825 to protect themselves from racist practices such as kidnapping Black people for the slave trade (Wall et al. 2008). Unfortunately, the term used for these white kidnappers was "blackbirders."

|

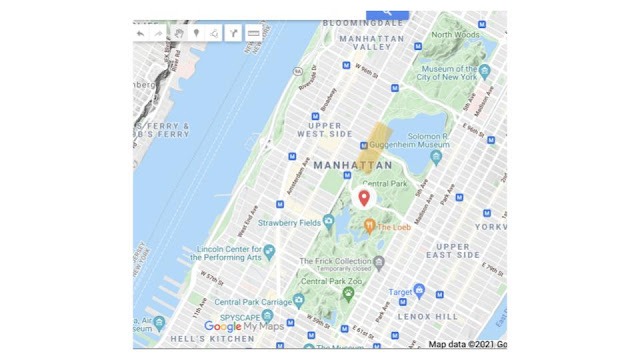

| Map of Central Park depicting Seneca Village (orange) and the Ramble (red pin) |

More than a century after Seneca Village was destroyed, an anti-Black incident occurred in the Ramble, a naturalized area of Central Park, which is in close proximity to the former enclave. To call out the hateful behavior and demand the right of African Americans to birdwatch safely, a group of Black birders launched Black Birders Week in 2020, which was followed by many Black in X weeks including Black Botanists Week. Participating in Black Botanists Week, and in BIPOC Hort, has changed my life. I am now part of

communities that center Black people and our experience and knowledge of plants. I found camaraderie and peers.

The Black Botanists Week organizing committee defined a botanist as a person who loves plants. This welcoming definition was an invitation for this non-botanist tree enthusiast. One of my favorite local trees is a centuries old English Elm in the northwest corner of Washington Square Park in New York City. The elm is admired by locals and tourists who pause to take in the tree's height and spread or to refresh themselves in the tree's deep shade. The elm also supports wildlife like raccoons (one was spotted sheltering in a cavity in 2018), squirrels, and birds (warblers, woodpeckers, and more). There is more to the elm's story, though.

When I began exploring Washington Square Park, I noticed the trees but could not find any digital resources about them. I spearheaded the creation of the park's first online tree map. My engagement with the park's trees has grown to include a phenology monitoring project. Beginning in fall 2019, neighborhood residents and university students track seasonal changes in 14 species representing 13 species. I get to flex my volunteer muscles by logging phenology data too! One goal of the project is to create phenology calendars for the trees in the park. A second goal is to provide community science opportunities through volunteering. Our third goal is to compare the park's phenology with other sites in the city to answer the question: how do leaf out, flowering and fruiting, and the appearance of colored leaves differ along an urbanization gradient in NYC?

My newfound plant home with Black Botanists Week inspired me to make a plantswoman "family tree." This lineage project is a work in progress but there are several Black women I think about when I think about plants. Nanny of the Maroons in Jamaica and Harriet Tubman here in the US used their understanding of forest ecology and natural resources to escape enslavement and to help others navigate to freedom. Kenyan, and Nobel Prize recipient, Wangari Maathai, PhD advocated for female-led forestry programs and mainstreamed the greenbelt. Recently I learned about Melody Mobley, the first Black woman to work for the US Forest Service in the role of professional forester. Dr. Dorceta Taylor, preeminent scholar on procedural injustice in the mainstream environmental movement, also studied botany. Dr. Carolyn Finney put a name to the experience of Black people in the outdoors with her book, Black Faces, White Spaces. White men like Carl Linnaeus, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Gifford Pinchot dominated the canon I read in college and graduate school. I am pleased to chart my own roll call of Black plantswomen.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for commenting on this post!